Property Law in Estonia

Estonia is, by its nature, a nation of property owners – which makes understanding property law essential.

Share of Homeowners and Market Shifts

Historically, personal ownership has been highly valued here, and homes are more often bought to live in than to rent out. While it used to be said that around 90% of people live in their own homes, more recent statistics put the figure closer to 79–80%. Yes, the vast majority of Estonians are homeowners, but the real estate market is constantly evolving.

In cities — especially Tallinn and Tartu — recent years have seen increased activity and rising prices in the rental market, making it less affordable for some to buy a home. At the same time, rental apartment buildings and long-term lease agreements are becoming more important. Across Estonia as a whole, however, the share of homeowners remains very high: roughly 80% of people live in a home they or their family members own.

Property Law in Estonia

Characteristics of Real Estate

Real estate is a unique type of asset with characteristics that set it apart from other forms of property. First, it is fixed and immovable — land and buildings cannot be moved. Second, real estate is often expensive, requires investment and upkeep, yet can generate income if used for renting or business. It also carries aesthetic and emotional value: a home can be cozy or modern, dignified or in need of renovation, private or prestigious. Alongside these practical aspects, real estate always comes with legal dimensions. Ownership can be inherited, gifted, and sold — but most importantly, real estate always entails rights and obligations.

Key Acts

A number of statutes govern Estonian property law. The most important is the Law of Property Act (AÕS), which defines principles of ownership, possession, and limited real rights. The Law of Property Act Implementation Act (AÕSRS) clarifies several issues, such as obligations to tolerate utility networks and the establishment of compulsory limited real rights. The Land Register Act regulates how entries are made in the land register and which principles apply there. The Apartment Ownership and Apartment Associations Act is crucial for residents and associations of apartment buildings. The Building Code and Planning Act influence construction and use permits and thereby the value and usability of real estate.

Roman Law and the Principle of Ownership

The Roman-law maxim superficies solo cedit — “what is on the land belongs to the owner of the land” — still underpins property law in many legal systems. In practice, this means buildings and structures permanently attached to the land (anchored to the ground, built structures, foundations, etc.) normally follow the ownership of the land. In Estonia, a similar approach appears via the right of superficies (ehitusõigus): the right to build on or use someone else’s land can be granted by agreement, but when that right ends or its conditions are not met, the building or structure may, in whole or in part, pass to the landowner. The principle is not absolute — important exceptions include apartment ownership, contractual arrangements, and rights of superficies defined by law — but it helps explain when land and structures form a single ownership unit.

The Land Register and Its Principles

The Land Register is a public register containing all Estonian immovables, together with owners, encumbrances, and mortgages, to ensure legal certainty in real estate transactions.

The land register is guided by several principles:

- Application principle – entries are made only on the basis of an application by the owner or a notary.

- Consent principle – all entitled parties must consent to changes.

- Priority principle – earlier entries rank ahead of later ones.

- Publicity principle – the register is open to inspection by interested persons with a legitimate interest.

- Public reliance (good-faith reliance) – third parties may rely on the register’s entries.

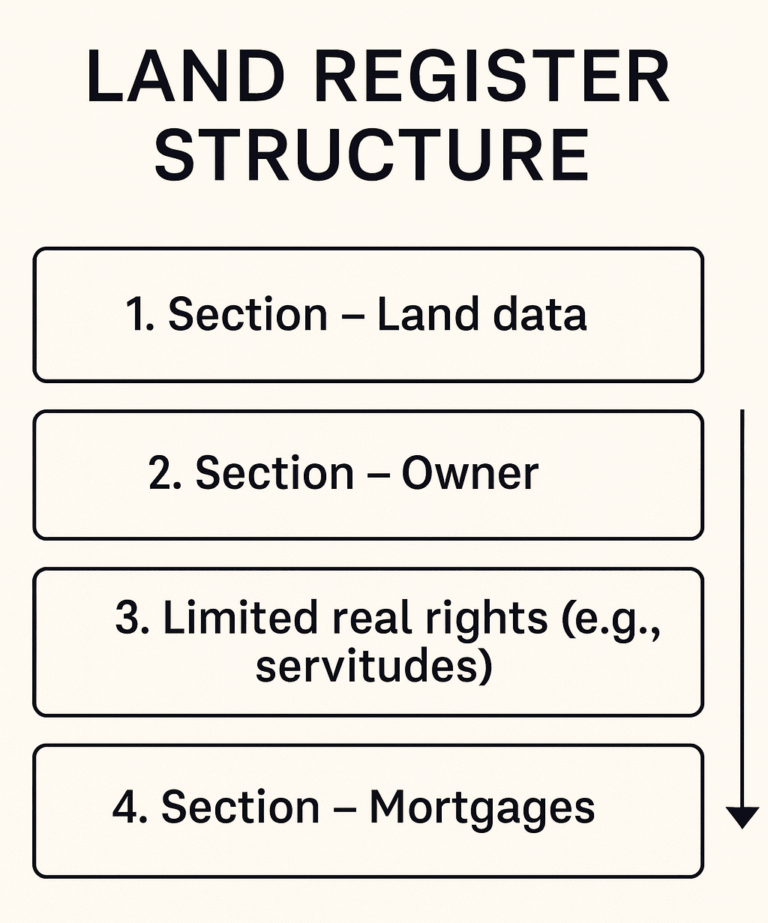

The land register has four divisions: (1) data about the parcel, (2) the owner, (3) limited real rights and other encumbrances (e.g., servitudes), and (4) mortgages.

The Land Register Act (KRS) regulates the keeping of the register, its structure, and the procedure for entries, including:

- what must be entered (land, owner, limited real rights, mortgages);

- how entries are made (e.g., on application, via a notary);

- which principles are followed (publicity, priority, etc.);

- the legal effect of the register (e.g., public reliance—data in the register may be trusted).

From Principles to Practice: Typical Property-Law Situations

Property law is not only about statutes and registry rules — it shows up in everyday situations and disputes faced by owners, tenants, and neighbors. Below we explain key topics such as acquisition in good faith, co-ownership, servitudes, compulsory limited real rights, neighbor law, and other questions that help avoid problems and ensure property is used safely and lawfully.

Acquisition in Good Faith

“Acquisition in good faith” means a person buys real estate honestly believing everything is in order, but later it turns out the seller had no right to sell. For example, the register may show one person as owner while an ownership dispute is ongoing or an entry has not yet been updated. If the buyer relied on the register and did not know — and was not required to know — that the seller lacked authority, the law protects the buyer: they remain the owner of the property.

This principle is vital for market certainty: people are willing to buy and sell real estate knowing that, if they act in good faith and check the land register, they will not be penalized for someone else’s mistake or hidden problem. It is a relatively rare scenario, but when it occurs it may involve substantial value and end up in court.

(Legal basis: Law of Property Act § 95.)

Co-Ownership

Co-ownership means a single property or building belongs to several persons at the same time. Each co-owner has an ideal (undivided) share of the whole, not a fixed physical part. By default, nobody owns “the kitchen” or “the yard” — everyone owns a proportional share of the entire property.

In practice, co-owners can agree on a notarised use arrangement that sets out who uses which parts (e.g., one uses the yard, another the garage, a third a particular flat). This supplements the undivided shares with a practical use split and helps avoid day-to-day disputes.

Problems arise if there is no use arrangement or one co-owner wants to make decisions without the others’ consent. If no agreement is possible, the law allows a co-owner to request termination of co-ownership. In practice this usually means one of three solutions:

- one co-owner buys out the others (or gifts their share away);

- the property is jointly sold to a third party and the proceeds are divided;

- the property is divided into apartment ownerships, if legally and structurally feasible.

Because co-ownership terminations often reach court, this is considered one of the more complex areas of property law.

(Legal basis: Law of Property Act § 70.)

Servitudes and Compulsory Limited Real Rights

Servitudes and compulsory limited real rights frequently arise in property use. Both involve situations where the owner must allow someone else to use the land or building — either by agreement or under law.

A servitude (servituut) is a right whereby the owner of one property (the “servient” property) must allow another person or property to use something. A straightforward example is a right of way: if a neighbor has no access to a public road, a servitude may grant the right to pass over another’s land. Servitudes can also allow utility lines — electric cables, water pipes — across a property. A servitude is typically created by agreement in a notarised deed and entered in the land register so it is visible and binding on future owners.

A compulsory limited real right (sundvaldus) is stronger and arises without the owner’s voluntary consent — through statute or an administrative act, in the public interest. For example, emergency services may require access for safety, or a network operator may need to install pipelines or power lines. The owner cannot block a compulsory right, but is generally entitled to compensation, since use of the property is restricted.

In short, a servitude is usually a negotiated solution, whereas a compulsory limited real right is a state or municipal obligation imposed for public purposes.

(Legal basis: Law of Property Act § 158; Law of Property Act Implementation Act § 15¹².)

Neighbor Law

Neighbor law sets rules to keep balance between neighbors when one property’s use affects another. While an owner is largely free to use their land, the law sets limits so that neighbors’ rights are not harmed.

Typical disputes involve smoke, noise, or dust affecting a neighboring plot; loss of sunlight due to tall trees or a building; and water runoff — if rain or meltwater is directed so that it floods the neighbor’s land, a court case can follow.

The law requires owners to exercise their rights with due regard to neighboring interests. A neighbor does not have to tolerate unreasonable harm or disturbance that exceeds normal limits. Disputes can be taken to court if needed.

(Legal basis: Law of Property Act § 143.)

Termination of Ownership of Real Estate

Ownership of real estate can end in two main ways. First, the owner may renounce the immovable. This is not done informally: a notarised declaration is required and entered in the land register. In that case, the property automatically passes to the state, and the state’s consent is not required for the entry.

(Legal basis: Law of Property Act § 126.)

Second, ownership may end via acquisitive prescription (usucapion). If someone else has used and possessed the immovable continuously and as if an owner for a long period — at least 30 years — they may, by law, become the new owner.

(Legal basis: Law of Property Act §§ 123–124.)

Acquisitive Prescription (Long-Term Possession)

Acquisitive prescription is a statutory route to ownership based on long-term possession and use as one’s own. In Estonia this generally requires 30 consecutive years.

Acting “as an owner” means caring for the property, paying land tax, maintaining or improving buildings, and not letting it fall into disrepair. Over that time, the true owner has not effectively asserted their rights or challenged the possessor’s actions.

Importantly, acquisitive prescription is not automatic. The possessor must apply to the court, and only after the court’s decision is the new owner entered in the land register. It exists to ensure legal certainty — to avoid immovables lingering indefinitely in unclear ownership.

(Legal basis: Law of Property Act §§ 123–124.)

The Hierarchy of Norms

Laws form a layered system in which some rules are general and others very specific. This is the hierarchy of norms.

General norms provide a broad framework. For example, the General Part of the Civil Code Act sets out overarching civil-law principles — general rules on transactions, time limits, abuse of rights, etc.

Special norms address specific situations or fields. The Law of Property Act governs ownership, limited real rights, servitudes, and mortgages, while the Implementation Act (AÕSRS) details matters such as obligations to tolerate utility networks.

When a general rule and a special rule collide — one says “as a rule do X,” the other says “in this specific case do Y”—the special rule prevails. This avoids confusion in a dense legal landscape and guides practice: first look for a specific provision; if there is none, apply the general one.

(Legal basis: General Part of the Civil Code Act; Law of Property Act Implementation Act.)

Property Law and Public/Private Law

Property law closely interlinks with both public and private law. It touches state planning, building permits, and public interests, as well as everyday life — families and neighbor relations. Understanding this maze matters to anyone buying, selling, managing, or using real estate. Legal awareness helps avoid costly problems and ensures property remains a safe, value-preserving investment.

(References: Building Code, Planning Act, Law of Property Act, Land Register Act.)

Estonian property law rests on strong traditions and well-considered statutes. Even so, disputes still arise in practice — especially regarding co-ownership, servitudes, acquisition in good faith, and neighbor law. Owners should keep an eye on legal developments, review registry entries and encumbrances, and consult a lawyer when needed — so their property serves their interests in the best possible way.